On my local Facebook page, a neighbor recently posted a photo of a beech tree. Taken from below, the picture revealed dark stripes banding across the tree’s green oval-shaped leaves.

My neighbor wanted to know what was ailing their tree. An informed commenter chimed in that it was suffering from Beech Leaf Disease (BLD), a relatively new affliction that has, over the last decade, spread from Ohio eastward to my home state of Massachusetts. The stripes were a clear indicator.

I began binge reading about the disease. Research is still in a fledgling state but scientists have identified that a nematode – a kind of parasite — is doing the damage. With each passing year, the leaves of infected trees deteriorate and branches begin to die off. BLD affects 90% of beech trees in affected areas, killing saplings in 2-5 years and mature trees in 6-10 years.

It’s decimating the beech tree population in a way we haven’t seen since Dutch Elm Disease or the American Chestnut Blight, which have all but wiped out those species of trees.

Morbidly curious, I closed my laptop and walked to the wetlands abutting my street to see how the beech trees there were faring.

Every beech tree I could find had leaves with that same striped pattern. There were at least a dozen impacted trees. I returned home and entered a tailspin of anxiety and mourning that took me by surprise.

The canopy of an affected Beech tree. Mike Munsell

Steve

My connection to beech trees dates back to the summer of 1996 when I met Steve, a new kid who had moved into my neighborhood and who quickly became my best friend. He was confident beyond his years and among the two or three funniest people I’m sure I will ever meet.

That same summer, we discovered Burgess Park, home to our local disc golf course, and we soon fell in love with the game. The course teemed with beautiful beech trees– each one with a smooth, light grey trunk that looked like the leg of an enormous elephant. Standing underneath and looking up toward the canopy, we half expected to see a great elephant trunk swinging down.

The trunk of a beech tree. Mike Munsell

Steve and I played disc golf together virtually every day – through wet springs and humid summers, in autumn, when it felt like we spent more time searching for our errant discs underneath piles of newly fallen leaves, and in wind-whipped winters for which we were perpetually underdressed.

Then in late high school Steve was diagnosed with a rare blood disorder, aplastic anemia – the same affliction that took the life of famed chemist Marie Curie. We were no longer able to play together so often.

With aplastic anemia, the body stops producing a healthy number of blood cells. It’s a bit of a mystery disease; in half of all diagnosed cases, the cause is unknown. The five-year survival rate is just 45%. It most frequently impacts teenagers and young adults – not far from their sapling years – just like Steve.

Steve died in 2006, two years after high school graduation and eight months before we could finally have a legal drink together.

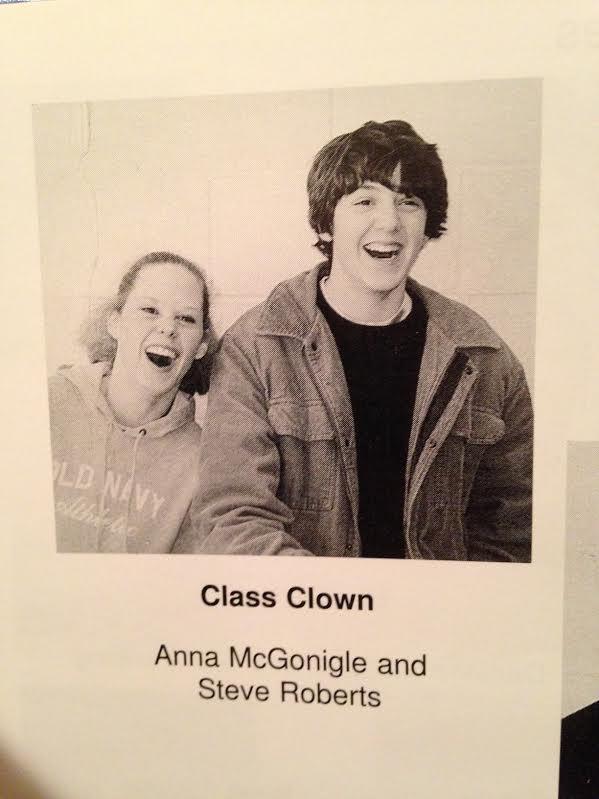

Steve’s high school superlative: Class Clown

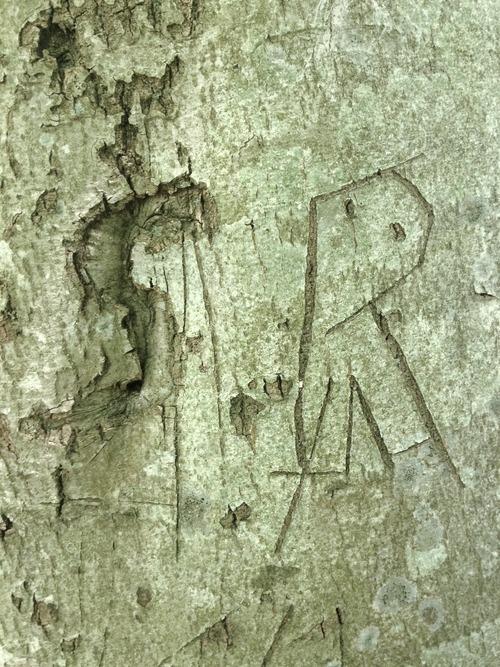

When I see a beech tree, I think of Burgess Park, and I think of Steve. There is one tree in particular, close to the shoreline of a pond that hugs the course, that Steve – then a middle schooler with an oversized and completely unnecessary hunting knife – etched with his initials (and yes, I know now that arborglyphs are harmful).

Losing beech trees to a disease that eats away at their leaves –disrupting their entire life system – that’s what had sent me to a dark place.

An expert opinion

After seeing infected trees by my house, I had so many questions. Will the beech tree go the way of the American chestnut tree? A tree that once numbered in billions, there only exist around 100 today due to disease and blight (though there is hope). Does climate change contribute to beech leaf disease? Are the trees at Burgess Park impacted? What about the one with Steve’s initials?

I decided to call up Nicole Keleher, the Forest Health Director of the State of Massachusetts. She said her phone has been ringing off the hook about BLD, so I told her I’d keep the call brief.

“It’s everywhere and in every county,” she said. “It’s moved through the state much faster than we had anticipated and it is starting to cause some severe decline in our beech trees.”

“It’s incredibly unusual”, Keleher continued. “A pathogenic foliar nematode in a woody plant is unheard of. There is no other disease that has functioned like this, so all of the research is starting from scratch.”

When I asked her if climate change was a factor, she said, “It’s hard to know because it’s such a new disease.”

“But when we have long periods of drought, increased storm events causing breakage and damage, and unstable temperature variations like the hard frost we had in May, that can be really stressful to trees. It’s not helping, even if it’s not the direct driver.”

Going home

Days after my call with Kelleher, I drove two hours south through Boston, over the Sagamore Bridge and onto Cape Cod – home to my youth, to Burgess Park, and to countless hours spent with Steve (including 24 consecutive hours spent in a swimming pool).

I played a round of disc golf with a small group of friends that used to play with me and Steve, plus two of my nephews that needed indoctrination into the sport.

Keleher was right. The disease had arrived in Barnstable county too. The leaves of the trees at Burgess Park showed the same striped patterns.

As we neared the tree with Steve’s initials, I felt a pit in my stomach.

My friends, nephews and I approached the tree, looked up, and saw those dark, telling stripes. My seven-year-old nephew suggested hugging the tree to see if it might help.

This beech tree – the one bearing the initials S.R. for Steven Roberts should live until 250 – but its life will be cut short by a disease that scientists barely understand. My young son, who shares a middle name with Steve, won’t be able to share a beer under the canopy of this tree, or the millions more just like it, when he comes of drinking age (or at least close to it).

A beech tree bearing Steve’s initials. Mike Munsell

And don’t get me started on the bears, foxes, squirrels, birds, and other wildlife that rely on beech trees as sources of food and housing. What happens to them in 6 to 10 years when the mature trees die off?

The last time I saw Steve was on hospice at Boston Children’s Hospital, which he had been in and out of since he was a teenager. I went alongside three more of his closest friends. His limbs brittle, Steve had wasted away to almost nothing, and we only exchanged a few words – in human speak anyways. With no energy left to talk but wanting to engage with us, Steve bent his arms into wings and chirped and cooed like a bird, all with a little smile on his face. We tweeted back with our own weird bird songs. Then we said our goodbyes and left.

Steve died a few days later.

Who’s to say what happens after you die? For all I know, Steve could be a bird now that has made its home in a beech tree, chirping a song in his own funny way.

In 2014, eight years after his death, and six years before Beech Leaf Disease would hit Massachusetts, a friend and I created a memorial site for Steve. I had written a short post about Burgess Park and the beech tree carving. In it, I wrote, “I hope the trees stand the test of time, and the carvings outlast us all.”

I still hope that, but I feel less certain about it by the day.

***

Postscript. The Mountain Goats’ song Matthew 21:25 brings me to tears every time I listen, transporting me back to the day we said goodbye to Steve at Boston Children’s.

And you were a presence full of light upon this earth

And I am a witness to your life and to its worth

Eloquently written

<

div>Can’t st

Thanks for writing this.